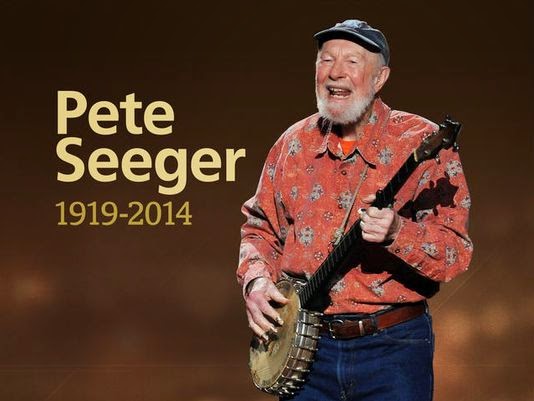

Remembering Pete Seeger -- Part One

A departure from my usual politically-charged fare -- sort of. I've been a guitar player and folk music lover for more than four decades. More recently, I took up the five-sting banjo. Music has been my companion in my teaching journey. And so has the wonderful spirit of Pete Seeger.

So let's write about that.

Im sure his biographers have struggled with how to begin to tell the story of Pete Seeger. The choices are endless. He was the son and step-son of accomplished musicians -- in particular, his father, Charles Seeger, was a pioneer of ethnomusicology. Pete would follow his father's path, albeit less academically, hopping freight trains with Woody Guthrie; recording and transcribing all-but-forgotten music on the backroads and in the backwoods of America with Alan Lomax; popularizing the twelve-string guitar (introduced to him by Lead Belly) and the five-string banjo; pioneering the long-kneck banjo; singing and playing for any audience that invited him. His legendary collaborations include The Almanac Singers, The Weavers, as well as long association with Arlo Guthrie, with whom he toured for the latter decades of his life. He was married to his beloved Toshi Seeger, with whom he had four children, for seventy years before her death in 2013.

One time of Pete's life that I find most intriguing was the blacklist era of McCarthyism, when Pete and many of his friends found themselves under the scrutiny of House Un-American Activities Committee. By this time, HUAC had already destroyed reputations and careers in Hollywood; now they were going after folk artists, the protest singers of the day.

Pete was called before the Committee, like other Americans, to testify about his affiliations. Seeger had been involved with the US branch of the Communist Party but drifted away in the late 1940s -- this is widely discussed in the second edition of an authorized biography How Can I Keep From Singing? -- The Ballad of Pete Seeger by David King Dunaway. At this time the Democratic Party was a far more conservative -- make that, regressive -- force, with Southern Democrats clinging to racial segregation as a way of life. The CPUSA called out to young Americans interested in race relations, women's rights, unions, international understanding, and demilitarization. Pete's father had abandoned the party some years before and begged Pete to follow suit. For a time Pete assumed that human rights abuses reported in Europe were anti-Communist propaganda.

The smoking gun the Committee had was evidence of Pete's appearance at a Communist rally. Following, an excerpt from the official transcript:

It was August 18th, 1955. Pete entered the hearing room with his banjo, which Toshi clutched while he testified. Going into the hearings, Pete had limited legal options. He could take refuge behind the Fifth Amendment which protects a witness against self-incrimination. He could take a soft fifth, a strategy used by other witnesses, in which he incriminates others, but not himself.

He could also answer the questions directly.

Seeger opted for another strategy that wasn't actually on the books. He decided to use the First Amendment, guaranteeing free expression, as his defence. He felt that was improper for the state to question him on his affiliations, any more than he should be questioned on how he voted.

The damage was done though. The resulting blacklisting kept Pete off television, an important medium for the musician and activist, for a decade. His and Toshi's decision years before -- to move the family away from the city and build a home in the woods of Beacon, New York -- was probably wise. Pete often wondered if someone would make an attempt on his life.

Here's an amazing reel from 1951 of Pete and The Weavers performing their chart-topping songs of the day. It opens with Tzena, Tzena, Tzena, sung in English and Hebrew. At 9:13, there's a touching tribute to Lead Belly. The Weavers had recorded his song Irene Goodnight with the plan of passing royalties onto the aging folksinger who was destitute and in poor health. Lead Belly died before the song became a huge hit, and the money went to his widow.

This 1947 feature, To Hear Your Banjo Play, was filmed by Alan Lomax, who also serves as off-camera interviewer. Pete is shown with such luminaries as Woody Guthrie, and Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee.

Up next. Tales of Pete on the road.

So let's write about that.

Im sure his biographers have struggled with how to begin to tell the story of Pete Seeger. The choices are endless. He was the son and step-son of accomplished musicians -- in particular, his father, Charles Seeger, was a pioneer of ethnomusicology. Pete would follow his father's path, albeit less academically, hopping freight trains with Woody Guthrie; recording and transcribing all-but-forgotten music on the backroads and in the backwoods of America with Alan Lomax; popularizing the twelve-string guitar (introduced to him by Lead Belly) and the five-string banjo; pioneering the long-kneck banjo; singing and playing for any audience that invited him. His legendary collaborations include The Almanac Singers, The Weavers, as well as long association with Arlo Guthrie, with whom he toured for the latter decades of his life. He was married to his beloved Toshi Seeger, with whom he had four children, for seventy years before her death in 2013.

One time of Pete's life that I find most intriguing was the blacklist era of McCarthyism, when Pete and many of his friends found themselves under the scrutiny of House Un-American Activities Committee. By this time, HUAC had already destroyed reputations and careers in Hollywood; now they were going after folk artists, the protest singers of the day.

Pete was called before the Committee, like other Americans, to testify about his affiliations. Seeger had been involved with the US branch of the Communist Party but drifted away in the late 1940s -- this is widely discussed in the second edition of an authorized biography How Can I Keep From Singing? -- The Ballad of Pete Seeger by David King Dunaway. At this time the Democratic Party was a far more conservative -- make that, regressive -- force, with Southern Democrats clinging to racial segregation as a way of life. The CPUSA called out to young Americans interested in race relations, women's rights, unions, international understanding, and demilitarization. Pete's father had abandoned the party some years before and begged Pete to follow suit. For a time Pete assumed that human rights abuses reported in Europe were anti-Communist propaganda.

The smoking gun the Committee had was evidence of Pete's appearance at a Communist rally. Following, an excerpt from the official transcript:

Mr. TAVENNER: I have before me a photostatic copy of the April 30, 1948, issue of the Daily Worker which carries under the same title of “What’s On,” an advertisement of a “May Day Rally: For Peace, Security and Democracy.” The advertisement states: “Are you in a fighting mood? Then attend the May Day rally.” Expert speakers are stated to be slated for the program, and then follows a statement, “Entertainment by Pete Seeger.” At the bottom appears this: “Auspices Essex County Communist Party,” and at the top, “Tonight, Newark, N.J.” Did you lend your talent to the Essex County Communist Party on the occasion indicated by this article from the Daily Worker?

It was August 18th, 1955. Pete entered the hearing room with his banjo, which Toshi clutched while he testified. Going into the hearings, Pete had limited legal options. He could take refuge behind the Fifth Amendment which protects a witness against self-incrimination. He could take a soft fifth, a strategy used by other witnesses, in which he incriminates others, but not himself.

He could also answer the questions directly.

Seeger opted for another strategy that wasn't actually on the books. He decided to use the First Amendment, guaranteeing free expression, as his defence. He felt that was improper for the state to question him on his affiliations, any more than he should be questioned on how he voted.

Mr. TAVENNER: It is a fact that he so testified. I want to know whether or not you were engaged in a similar type of service to the Communist Party in entertaining at these features.(Witness consulted with counsel.)

Mr. SEEGER: I have sung for Americans of every political persuasion, and I am proud that I never refuse to sing to an audience, no matter what religion or color of their skin, or situation in life. I have sung in hobo jungles, and I have sung for the Rockefellers, and I am proud that I have never refused to sing for anybody. That is the only answer I can give along that line.

...

Mr. SEEGER: I will tell you what my answer is. I feel that in my whole life I have never done anything of any conspiratorial nature and I resent very much and very deeply the implication of being called before this Committee that in some way because my opinions may be different from yours, or yours, Mr. Willis, or yours, Mr. Scherer, that I am any less of an American than anybody else. I love my country very deeply, sir.

Chairman WALTER: Why don’t you make a little contribution toward preserving its institutions?

Mr. SEEGER: I feel that my whole life is a contribution. That is why I would like to tell you about it.

Chairman WALTER: I don’t want to hear about it.Pete later acknowledged the recklessness of the ploy. However honourable, he had irritated some powerful men and found himself convicted of nine counts of Contempt of Congress in 1961 -- each one carrying a one-year term in prison to be carried out consecutively. Because his conviction hearing was found to be legally flawed, he escaped prosecution in 1962.

The damage was done though. The resulting blacklisting kept Pete off television, an important medium for the musician and activist, for a decade. His and Toshi's decision years before -- to move the family away from the city and build a home in the woods of Beacon, New York -- was probably wise. Pete often wondered if someone would make an attempt on his life.

Here's an amazing reel from 1951 of Pete and The Weavers performing their chart-topping songs of the day. It opens with Tzena, Tzena, Tzena, sung in English and Hebrew. At 9:13, there's a touching tribute to Lead Belly. The Weavers had recorded his song Irene Goodnight with the plan of passing royalties onto the aging folksinger who was destitute and in poor health. Lead Belly died before the song became a huge hit, and the money went to his widow.

This 1947 feature, To Hear Your Banjo Play, was filmed by Alan Lomax, who also serves as off-camera interviewer. Pete is shown with such luminaries as Woody Guthrie, and Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee.

Up next. Tales of Pete on the road.

Comments

Post a Comment